Saturday, March 19, 2011

Sunday, August 29, 2010

CARROLL SHELBY COBRA GT 350/500 | KING OF THE ROAD

Saturday, July 17, 2010

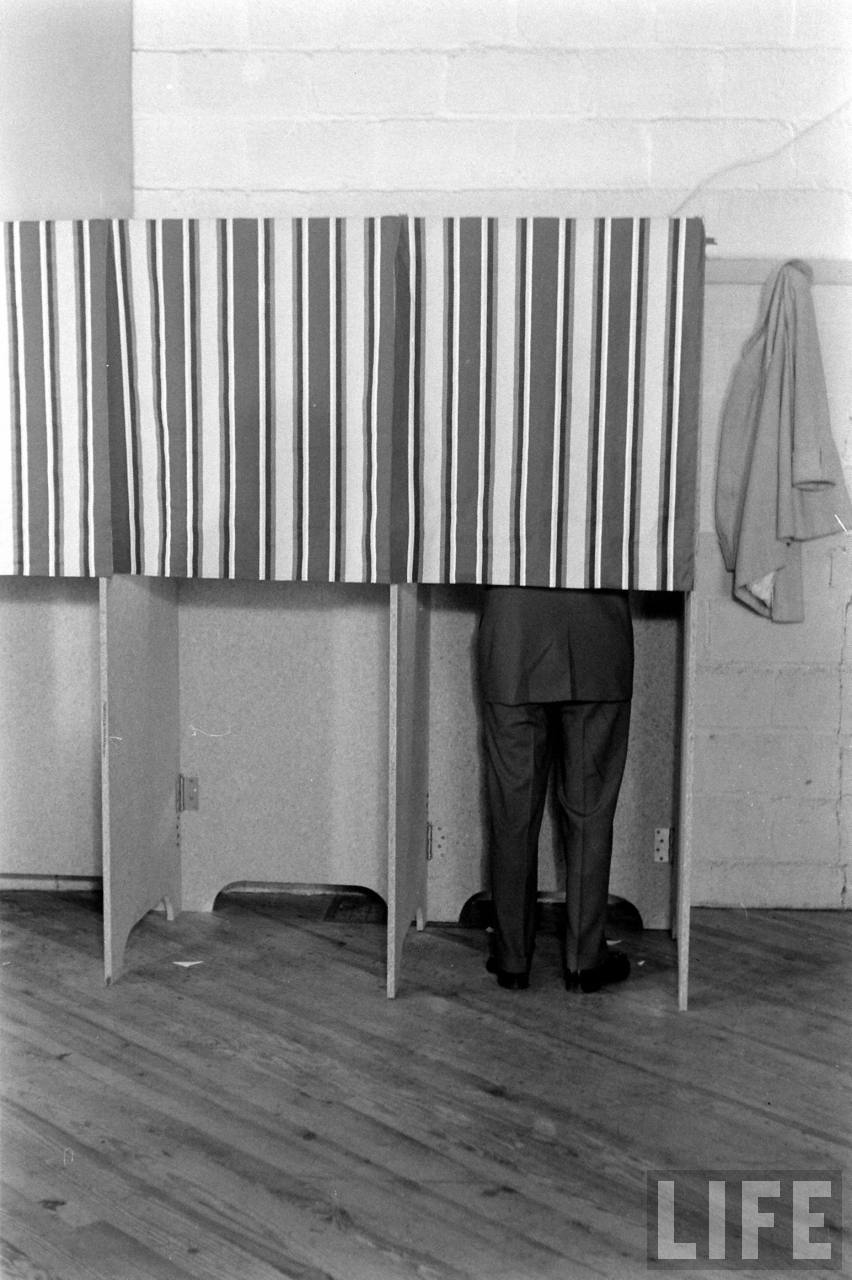

ROCK THE VOTE | SUPPORT TSY IN THE DETAILS MAG FASHION BLOG AWARDS

BE HEARD AND CAST YOUR VOTE IN SUPPORT OF TSY, CLICK HERE!

TSY is honored to be nominated, and is up against some very stiff competition. If you love what we do here, and would like to support us by voting-- we'd really appreciate it, friends!

Martha's Vineyard locals cast their vote for TSY in an epic show of support. --LIFE archives

Ike casts his vote for TSY in Gettsyburg. --LIFE archives.

Avid Detroit supporters lining up outside the fire station to vote for The Selvedge Yard --LIFE archives

Sunday, February 7, 2010

STEVE McQUEEN GOES FOR BROKE IN THE ROUGH LIFE, 1963 | "IF YOU CAN'T CUT IT, YOU GOTTA BACK OUT."

Wincing, Steve McQueen gets his blistered hands treated in Pearblossom, Calif. Steve says of his dangerous sport, "If you can't cut it, you gotta back out."

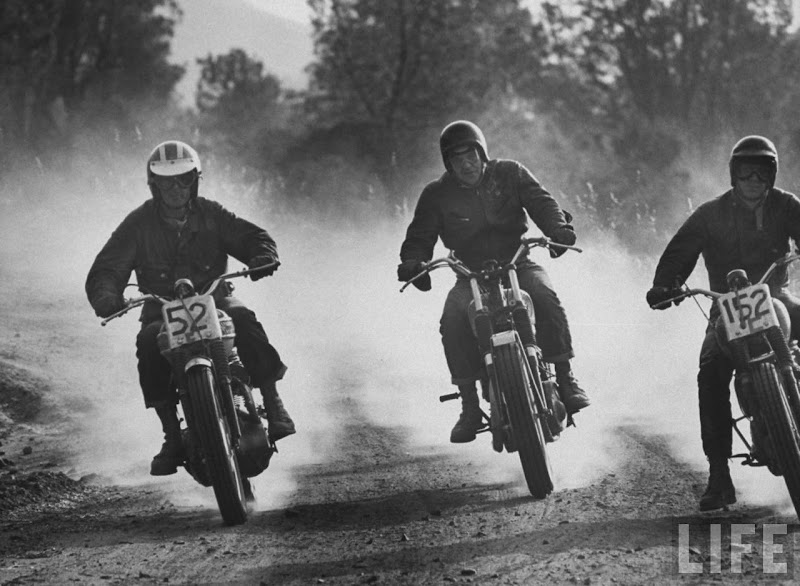

Rounding a bend in a cross-country motorcycle race, Steve McQueen (right) a long-time racer, keeps up a torrid pace. He was one of 300 entrants. The race took 2 days, went across the Mojave Desert.

The race over, Steve McQueen wearily puts on his jacket after a brief cooling-off. He led the amateur class until his motorcycle broke down three miles from the finish.

Looking like a helmeted James Cagney, Steve McQueen talks with his buddies during a respite. A crack auto racer, he even raced with Stirling Moss-- but he gave up the sport to please his wife.

On a camping trip in the Sierra Madre, Steve McQueen is rudely awakened by his dog Mike, a Malamute. He often takes his whole family along on camping trips, but this time went with old buddies. "This is it, man" says Steve. "I'd rather wake up in the middle of nowhere than in any city on earth."

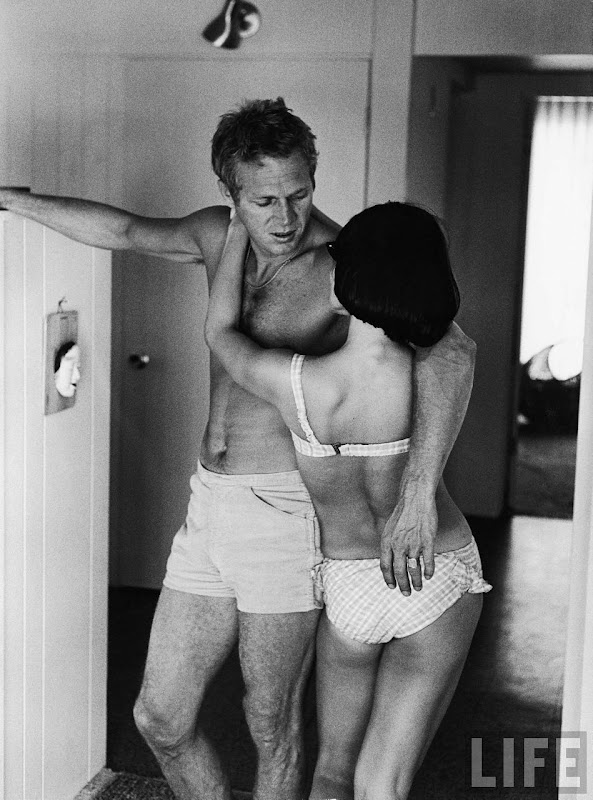

In their Palm Springs bungalow, Steve McQueen and his wife Neile chat affectionately.

"Man, if I hadn't made my own scene," says Steve McQueen, "I could have wound up a hood instead of an actor." He talks the lingo of the rough world that spawned him-- a world of hipsters, race car drivers, beach boys, drifters, and carnival barkers. Steve has been al of these. He has also tended bar, sold encyclopedias, made sandals, and even been a runner in a Port Arthur, TX brothel-- going from one job to the next, trying to run from his dreary, dreadful past.

Steve has been running that way ever since he was a kid. His father began it by running out on the family while Steve was still a baby. Mrs. McQueen farmed Steve out to an Uncle in Missouri. At 12 Steve fled to New York. He later lived with his mother and new stepfather in California, but that was no improvement. He spent so much time on the streets, and so little time in school, that his mother sent him away for rehabilitation. He promptly ran away and wound up in jail. Even in the Marines, Steve McQueen wouldn't stay put-- he spent 41 days in the brig for going AWOL.

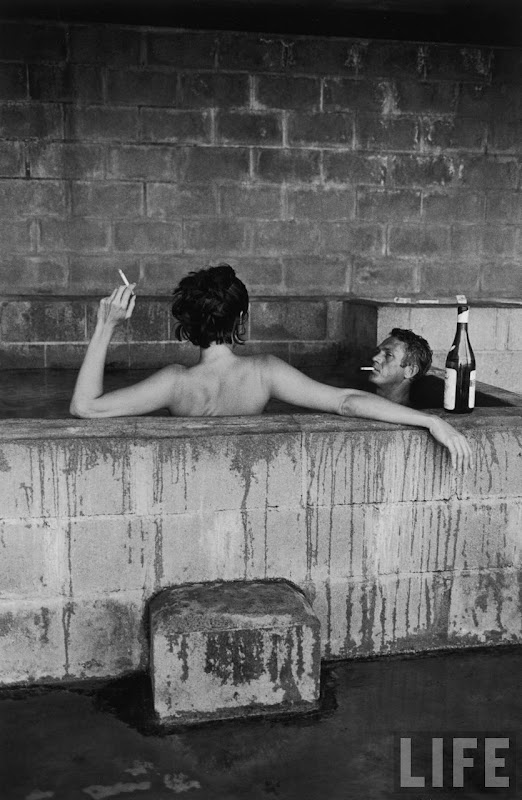

At Big Sur, Steve McQueen and Neile take a sulphur bath together, a bottle of wine propped nearby.

He was in New York in 1951, working as a bartender, when a friend took him along with her to an acting school. Willing to try anything, he auditioned there, and to his astonishment was accepted.

"I took up acting," he explains, "because it let e burn off energy. Besides, I wanted to beat the 40-hour-a-week rap. But, Man, I didn't escape. Now I'm working 72 hours a week, so there you go."

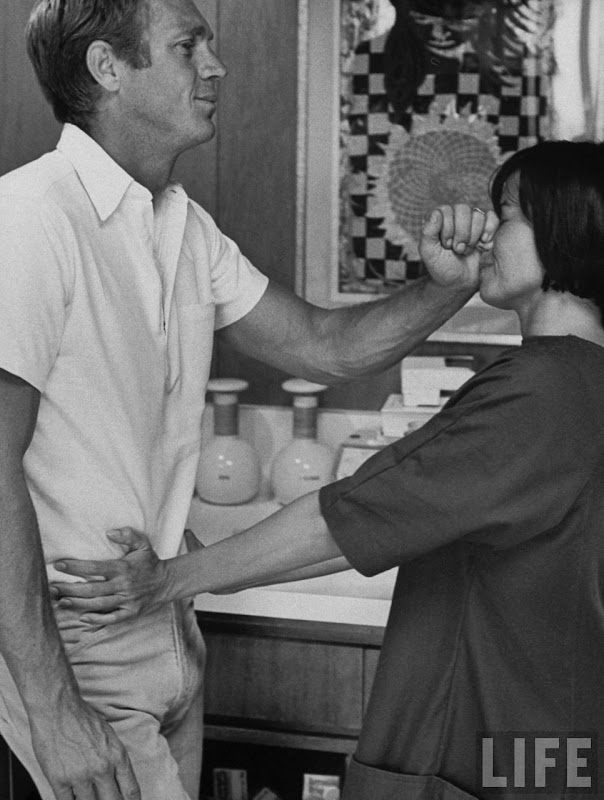

While waiting in the kitchen for Neile to serve up a snack, Steve gives her a fond tweak.

Steve McQueen works at acting with the same urgency that he races motorcycles. "I'm the greatest scammer in the business," says Steve. "But acting's a hard scene for me. Every script I get is an enemy I have to conquer."

But he shuns the duties that go with being a movie star. He seldom attends parties or nightclubs, and sulks at movie premieres. "When I get in a room with five strangers, that's my nut," he says, "I feel like I can't breathe, O.K.?"

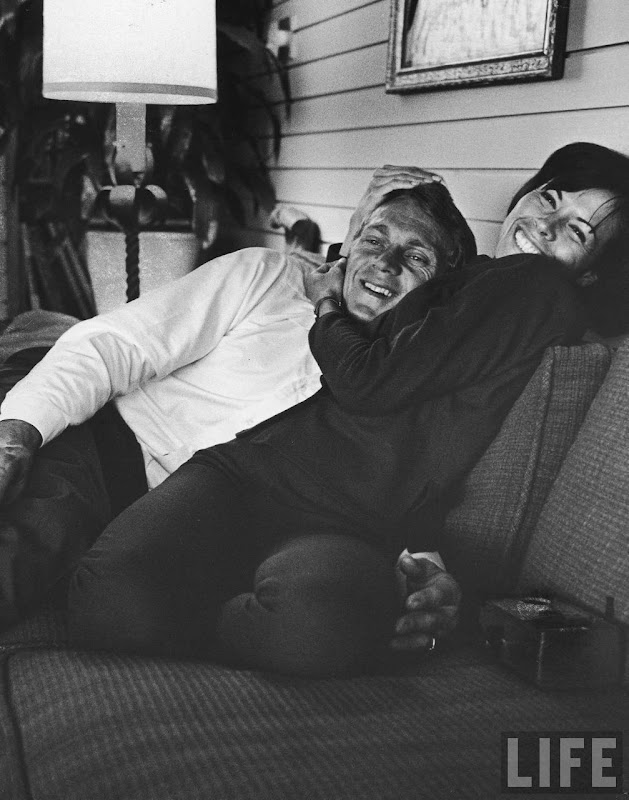

Steve McQueen cozies up with his wife Neile, who is of English, German, Spanish and Chinese descent. They met when she was on Broadway in Pajama Game. Says he, "My old lady is the heart of my home."

Steve McQueen cozies up with his wife Neile, who is of English, German, Spanish and Chinese descent. They met when she was on Broadway in Pajama Game. Says he, "My old lady is the heart of my home." When he is with his wife and children, Steve McQueen quickly gets his breath back. Though married seven years, the McQueens are still as lovey-dovey as newlyweds. "When I come home nights," says Steve, "I dig my old lady, not the maid, serving me dinner."

Others he digs are hard-luck characters who, like him, drew a raw deal, and he tries to help them. "When you take a little out," Steve explains, "you gotta put a little back in." He and Dr. Herman Salk, a Palm Springs veterinarian who is Jonas Salk's brother, raise money to buy vaccines and antibiotics for Navajo Indians. Periodically they drive to the reservation to deliver the drugs. "I really dig those Navajos," says Steve. "They have a saying they live by: A land where there is time enough and room enough. I want that too."

Steve McQueen, who delights in giving his son the love he lacked while growing up, romps with Chad, 2.

Steve McQueen, who delights in giving his son the love he lacked while growing up, romps with Chad, 2.Last week Steve McQueen bought a three-acre, quarter-million-dollar mansion overlooking the Pacific. "It's got trees for the kids to swing on," he says, voice all aquiver, "and the biggest, strongest front gate you ever saw. Man, I don't wanna be bugged by anyone, O.K.?"

But once there, Steve is likely to want out. It is too near Hollywood. "You won't find me hanging by my toes in a manhole," he promises. "Man, after I've gotten my sugar out of this business, I'm gonna take off-- and run like a thief."

-Peter Bunzel, photos by John Dominis, 1963.

In a rented tuxedo (he does not own one), Steve McQueen gives a goodnight kiss to Terry, 4, before making one of his rare appearances at at Hollywood opening. "My family is very, very tight." says McQueen. "But the world is full of phonies, so you gotta build a wall to keep them out."

In a rented tuxedo (he does not own one), Steve McQueen gives a goodnight kiss to Terry, 4, before making one of his rare appearances at at Hollywood opening. "My family is very, very tight." says McQueen. "But the world is full of phonies, so you gotta build a wall to keep them out."

Labels:

1960s,

1963,

AUTO,

Hollywood,

LIFE ARCHIVE,

magazine,

MOTORCYCLE,

RACING,

STEVE MCQUEEN

Friday, January 1, 2010

STEVE McQUEEN DOIN' IT IN THE DIRT AND DUNES | THE TRIUMPH DESERT RACE BIKE CUSTOM MODIFIED BY BUD EKINS.

Nostalgia on Wheels posted these incredible pictures of Steve McQueen and his Bud Ekins' desert-modified Triumph Bonneville racer from the June 1964 edition of Cycle World Magazine. Original photos by Cal West.

Actor Steve McQueen and his Triumph desert bike in their native habitat.

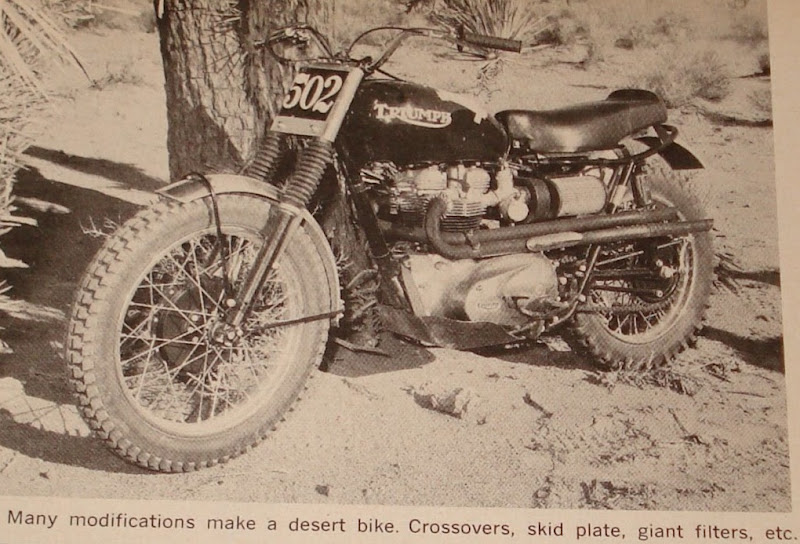

Many modifications make a desert bike. Crossovers, skid plate, giant filters, etc.

Paper-pack air cleaners are connected to carbs by special a collector box. A Cushy saddle and high pipes are essential in the desert.

IN McQUEEN'S SERVICE

Winning desert races is what this machine was set up for. It is the mount of actor Steve McQueen, who recently won the novice class in a one-hour desert scrambles. The victory only proved what a close look at his Triumph Bonneville suggests: McQueen takes his motorcycling seriously.

It takes some modifications to wing the rough, dusty hare 'n hounds, scrambles and enduros that are popular in the southwestern desert. McQueen's machine was prepared in Bud Ekins' Sherman Oaks, California shop. They started by replacing the stock wheel with a 1956 Triumph hub and 19" wheel to reduce unsprung weight. The forks were fitted with sidecar springs and the rake increased slightly by altering the frame at the steering crown. The rear frame hoop was bent upward to accommodate a 4.00 x 18 Dunlop sports knobby, and to it were welded brackets for the Bates cross-country seat. The bars are by Flanders, with leather hand guards, and the throttle cables run over the tank, through alloy brackets to the twin 1 1/8" Amal carburetors.

A Harlan skidplate protects the underside of the motor, the footpegs were braced, and the rear brake rod was increased to 5/16" diameter and rerouted inside the frame and shock (where sagebrush can't damege it). The oil tank was modified to increase its capacity and bring the filler out the side fom under the seat. It also serves as part of the mudguard, saving weight.

The engine is basically a stock Bonneville but the compression was lowered from 12 : 1 to 8 1/2 : 1 for reliability, and the sagebrush-snagging oil pressure indicator was converted t a pop-off relief valve with a return line back to the oil tank. McQueen runs Jomo TT cams and Lode RL47 Platinum tip plugs.

The important job of filtering all that dirt out of the desert air is handled by paper-pack air cleaners connected by a special collector box to the carbs. This box is finished in black wrinkle-finish paint while the tanks are dark green. The cross-over pipes are Ekins' own design, and are left unplated for better heat dissipation. Perhaps if McQueen were riding this motorcycle in the movie, he would have made his "Great Escape."

--Cycle World Magazine, June 1964

Labels:

1960s,

1964,

BUD EKINS,

DESERT,

HISTORY,

MOTORCYCLE,

RACING,

STEVE MCQUEEN,

TRIUMPH,

VINTAGE

Saturday, November 21, 2009

KENNY HOWARD PT. II | THE MASTER PAINTER, STRIPER & CUSTOM FABRICATOR ALSO KNOWN AS VON DUTCH

What Ever Happened to Von Dutch? --Modern Cycle magazine, 1965

WORLD FAMOUS BODY STRIPER NOW "IN HIDING" AT SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CYCLE SHOP.

Automotive striping, whether for motorcycles or cars, was a dead art form in this country when 15-year-old Von Dutch went to work in George Beerup's motorcycle shop back in the mid forties. Six or seven years later is was a thriving trade carried on by several hundred artistically inclined body men around the country, and no self-respecting Hot Rodder would consider his customizing finished until the striping had been put on.

Few people realize that striping, even to this day is strictly a hand craft. At the Triumph factory, for instance, one elderly gentleman who appears to have been with the company for a century, spends his working day doing nothing but placing the finishing stripes o fenders and fuel tanks by hand. The same is true at the Enfield works... and the Rolls Royce works.

The last automobile hand striping by American car makers was done by General Motors cars in 1938 (excluding, of course, any special bodies created later). Then, nearly 20 years later, youthful car customers brought it back in vogue with some outlandish designs, often believing they were doing something entirely new. The man who started the vogue was a young motorcycle mechanic named Von Dutch.

Today Dutch is "in hiding" as a result of the reputation he built. Working as a mechanic once again, he'll do an occasional striping job on a fender or a tank for a friend. But he made us promise not to identify the shop where he works because "I don't want any damn kids around here trying to get me to stripe their cars."

DUTCH STRIPES WITHOUT ANY PLANNING WHATSOEVER. HE DID THIS JOB IN APPROXIMATELY 10 MINUTES, TALKING CONSTANTLY WITH PHOTOGRAPHER JIM SULLIVAN. DUTCH DIPS HIS DAGGER STRIPING BRUSH ON HIS FAVORITE PALET, THE TELEPHONE BOOK.

At 15, Von Dutch was what he called "the gunk boy" in George Beerup's motorcycle shop in Southern California when he took one of the bikes home, painted it and striped it with his father's brushes. (The elder Von Dutch had done some motorcycle striping and worked mostly as a sign painter.) When he brought the bike back, Beerup refused to believe he had done the striping himself. So he got the brushes and did another job. As soon as Beerup saw what he could do, he took Dutch off mechanical work and put him to painting and striping, and for the next decade he built a reputation he didn't want.

"I'm a mechanic first," he says. "If I had my way, I'd be a gunsmith, but there isn't enough of that kind of work to make a living. I like to make things out of metal, because metal is forever. When you paint something, how long does it last? A few years, and then it's gone."

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES. ABOVE RIGHT: ANOTHER OF DUTCH'S DREAMS, UTILIZING A 750cc INLINE FOUR WITH "OFFENHAUSER CHARACTERISTICS," EARLES TYPE FORKS AND THE SWING ARM OF CAST MAGNESIUM FORMING A CHAIN CASE, THE WHOLE AFAIR SWINGING ON THE AXIS OF THE COUNTERSHAFT TO ELIMINATE CHAIN DEFLECTION.

ABOVE, BOTTOM: DUTCH ON HIS BABY, A 1930 SCOTT "FLYING SQUIRREL" 600cc WATER COOLED TWO STROKER. With 5 1/:1 COMPRESSION IT DEVELOPS 33 hp AT 4500 rpm. COMPLETELY RESTORED, IT IS UNMODIFIED EXCEPT FOR A SEPARATE OIL TANK, SUPPLYING LUBRICANT UNDER PRESSURE TO MAINS AND CRANKPINS.

For the next several years, Dutch worked at nothing but motorcycle painting and striping moving from shop to shop, "saturating each area," he says. By the mid fifties he had still not touched a car, but had painted and striped thousands of bikes. After a year or so of building his reputation,

"Striping cars started as a gag when I was working Al Titus' motorcycle shop down in Lynwood," Dutch says. Then the idea ballooned. He was hired to stripe some custom jobs for one of the auto shows, an while there was approached by a man known as the Crazy Arab who thought it could be worked into a full time occupation. Dutch didn't believe it, but he tried it, and for the next three years he worked at it until "it nearly drove me out of my mind."

When Von Dutch quit striping around 1958, his talents were still in great demand. Customers all over the country had heard of him, and cars had come as far away as the East Coast to be striped. Moreover, when a car owner came to him, he didn't tell Dutch what he wanted: he just told him how much time he was willing to purchase. The designs were up to Dutch, and some of them were as wild and far out as his eccentric imagination. He had hundreds of imitators, and when you went to a body shop to inquire about such work, you didn't ask if they knew how to stripe, you asked if they knew how to "Von Dutch."

Despite this, Dutch never made any money from striping, because money is something he hates, as unorthodox as that sounds. After a year or so of building his reputation, he doubled his hourly rate just to weed out some of the customers. So many were coming to him that he couldn't stand it anymore. But the gambit didn't work. No matter how much he charged, he still did better work for less money than any competitor.

He could have charged much more. He could have charged $20 an hour and gotten away with it easily back then. Moreover, he could have done six or eight cars a day, if he really wanted to work at all. But Dutch is blissfully devoid of the driving force that motivates most Americans. He couldn't care less about material possessions.

"I make a point of staying right at the bridge of poverty. I don't have a pair of pants without a hole in them, and the only pair of boots I own are the ones I have on. I don't have anything else to put on my feet. I don't spend money on unnecessary stuff, so i don't have to have a lot of money. I don't need it. I keep as poor as I can and just get along. I like that. I believe that's the way it's meant to be. There's a struggle you have to go through, and if you make a lot of money, it doesn't make the struggle go away. It just makes it more complicated. If you keep poor, the struggle is simple. "

"That's why I never overcharged anybody, or made this thing commercial. You can't do good work if you're thinking about the money angle all the time. To me the work is important; that's number one."

Most of Dutch's custom work is now done exclusively on antique motorcycles belonging to the shop where he works. The shop is not known to have a painting department, but a fellow in North Carolina, who knew where to go, sent them a tank and fenders from a brand new Triumph to be painted as they saw fit, and Dutch did the work.

Dutch's personal motorcycle is a 1930 Scott twin, a two stroke water-cooled job that most motorcycle enthusiasts had never heard of. When something wears out on it, he manufactures the part himself. He also has a customized Honda, of which he says, "I had to paint it so I could find it. There are so many around that mine was getting lost in the crowd."

Dutch's whole life is more or less devoted to individualism, to expressing himself. He says he can no longer take paint work as a steady diet, but once you get him started on a project, you can't stop him until his imagination is temporarily worn out. He takes plain metal and turns it into a gun of his own design. Lately, he has taken to engraving designs on Aluminum fenders.

There seems to be no end to his creative aptitudes, despite his refusal to use them for profit. One of his co-workers calls him "That artistic creep," but in may ways he's the Einstein of the motor world.

Friday, October 30, 2009

HUSQVARNA | THE SCREAMIN' SWEDE SUPER-BIKE THAT STARTED A MOTORCYCLE RACING REVOLUTION

The bike that got American motocross off the ground-- the 1963 Husqvarna (Husky) Racer. This unrestored bike is No. 59 of just 100 250cc race machines Husqvarna built in ’63.

With its signature red and chrome glistening gas tank, the Husqvarna (or “Husky” as it’s affectionately known) was a stunning beauty of a bike, and a mud-slinging beast on the American motocross circuit. Back in the 1960s, the increasingly popular sport of American motocross was bogged down by clumsily modified (not to mention heavy) Harley-Davidson, Triumph & BSA road bikes. It was lumbering in antiquity and in dire need of innovation. Enter Edison Dye.

While on a motorcycle tour of Europe, Dye took particular note of European motocross and the lighter-weight, nimble, two-stroke bikes that were in stark contrast to the American scene. Swedish maker Husqvarna particulary stood out with their alloy engine components, and distinctive exhaust. He asked motorcycling legend Malcolm Smith (Steve McQueen’s riding chum in “On Any Sunday”) to take a Husky and put it through its paces for him. Upon Smith’s glowing review, Edison Dye decided to sign on as Husqvarna’s U.S. importer. The Screamin’ Swede was about to take American motocross by storm.

Heikki Mikkola, the “Flyin’ Finn” was one of the most popular and feared motocross racers of the 1970s. During his illustrious career, Mikkola collected four World Grand Prix Motocross Championship titles. In 1974 he won the World Grand Prix 500cc Championship on a Husqvarna.

In the early 1970s, Steve McQueen was the man (still is). He was the highest-paid star of the silver screen, a major sex symbol and an obsessed motorhead with a staggering collection of sports cars, four-wheelers and of course– bikes. So when McQueen dropped his trusty Triumph in favor of the new Husqvarna 400 Cross – overnight Husky became the only off-road bike that seemed to matter. The Husky also got a starring role alongside Steve McQueen (as well as riding legends Mert Lawwill and Malcolm Smith) in Director Bruce Brown’s classic– ”On Any Sunday”.

Bruce Brown recounts working with McQueen and the significant impact the film had–

“I remember going to Ascot Park and watching the dirt track races,” Brown said. “I met a few of the racers and was struck by how approachable and how nice most of these guys were. It wasn’t at all like the image a lot of people had about motorcycle riders in those days. I just thought it would be neat to do a movie about motorcycle racing and the people involved.”

Even though Brown already had a successful movie to his credit, he found that financing a film on motorcycling wasn’t going to be easy.

The Husqvarna 400 Cross-- The bike Steve McQueen made an overnight legend, and highly collectible.

“I talked to a few folks and knew that Steve McQueen was a rider,” Brown said. “Even though I’d never met him, I set up a meeting to talk about doing ‘On Any Sunday.’ We talked about the concept of the film, which he really liked. Then he asked what I wanted him to do in the film. I told him I wanted him to finance it. He laughed and told me he acted in films, he didn’t finance them. I then jokingly told him, ‘Alright, then, you can’t be in the movie.’

“The next day after the meeting, I got a call and it was McQueen. He told me to go ahead and get the ball rolling with movie — he’d back it.”

At one point, Brown found a perfect location for a sunset beach riding shot — Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base.

“I figured there would be no way to get approval to film on the Marine base,” Brown recalls. “Steve McQueen said he’d see what he could find out. The next day he called and told to contact some General and the next thing you know we are shooting the beach sequences. It was pretty amazing the doors he was able to open.”

“On Any Sunday” seemed to strike a chord with youngsters. Kids would hide in movie theater bathrooms between showings so they could watch the film two or three times in one day. Thousands of kids across the country started saving money from their paper routes and summer jobs to buy a minibike after being inspired by the movie.

1970 Husqvarna 250 eight-speed, just like the one ridden by Malcolm Smith in”On Any Sunday”. “The Husky 250 eight-speed was just a really easy bike to ride,” Smith recalls. “It wasn’t super powerful, but on the fast roads of Elsinore, I could go over 100 mph. And because of the eight-speed gearbox, I could easily negotiate the tight stuff.”

“I think many people changed their minds about motorcyclists after watching the movie,” Brown said. “One particularly funny story was told by Mert Lawwill. Being a motorcycle racer he was sort of considered the Black Sheep of the family. The old patriarch of the family, Lawwill’s grandmother-in-law, went to see the movie and in the middle of one of the scenes featuring Lawwill she stood up and shouted, ‘That’s my grandson!’ Suddenly he was the big hero of the family.”

Malcolm Smith flat-out gettin’ after it, Husqvarna style.

Steve McQueen on his Husqvarna 1971 400cc Cross. This is the bike that Steve rode on screen -- "On Any Sunday".

Steve McQueen romping on his Husqvarna 400 Cross –Sports Illustrated, 1971.

The legendary motorcyclist and Husqvarna rider– Malcolm Smith.

Wrenchmonkees’ insane flat track inspired Harley Davidson Sportster with an old Husqvarna tank.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)