What Ever Happened to Von Dutch? --Modern Cycle magazine, 1965

WORLD FAMOUS BODY STRIPER NOW "IN HIDING" AT SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CYCLE SHOP.

Automotive striping, whether for motorcycles or cars, was a dead art form in this country when 15-year-old Von Dutch went to work in George Beerup's motorcycle shop back in the mid forties. Six or seven years later is was a thriving trade carried on by several hundred artistically inclined body men around the country, and no self-respecting Hot Rodder would consider his customizing finished until the striping had been put on.

Few people realize that striping, even to this day is strictly a hand craft. At the Triumph factory, for instance, one elderly gentleman who appears to have been with the company for a century, spends his working day doing nothing but placing the finishing stripes o fenders and fuel tanks by hand. The same is true at the Enfield works... and the Rolls Royce works.

The last automobile hand striping by American car makers was done by General Motors cars in 1938 (excluding, of course, any special bodies created later). Then, nearly 20 years later, youthful car customers brought it back in vogue with some outlandish designs, often believing they were doing something entirely new. The man who started the vogue was a young motorcycle mechanic named Von Dutch.

Today Dutch is "in hiding" as a result of the reputation he built. Working as a mechanic once again, he'll do an occasional striping job on a fender or a tank for a friend. But he made us promise not to identify the shop where he works because "I don't want any damn kids around here trying to get me to stripe their cars."

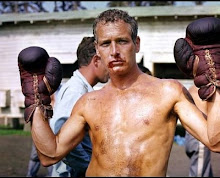

DUTCH STRIPES WITHOUT ANY PLANNING WHATSOEVER. HE DID THIS JOB IN APPROXIMATELY 10 MINUTES, TALKING CONSTANTLY WITH PHOTOGRAPHER JIM SULLIVAN. DUTCH DIPS HIS DAGGER STRIPING BRUSH ON HIS FAVORITE PALET, THE TELEPHONE BOOK.

At 15, Von Dutch was what he called "the gunk boy" in George Beerup's motorcycle shop in Southern California when he took one of the bikes home, painted it and striped it with his father's brushes. (The elder Von Dutch had done some motorcycle striping and worked mostly as a sign painter.) When he brought the bike back, Beerup refused to believe he had done the striping himself. So he got the brushes and did another job. As soon as Beerup saw what he could do, he took Dutch off mechanical work and put him to painting and striping, and for the next decade he built a reputation he didn't want.

"I'm a mechanic first," he says. "If I had my way, I'd be a gunsmith, but there isn't enough of that kind of work to make a living. I like to make things out of metal, because metal is forever. When you paint something, how long does it last? A few years, and then it's gone."

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES.

ABOVE, TOP: IN CASE YOU DON'T RECOGNIZE IT, THAT'S AN M-1 DUTCH IS POLISHING. THIS IS DUTCH'S IDEA FOR A SCOTT-POWERED MACHINE USING REYNOLDS TYPE FORKS AND MODERN REAR SUSPENSION, WITH DISC BRAKES. ABOVE RIGHT: ANOTHER OF DUTCH'S DREAMS, UTILIZING A 750cc INLINE FOUR WITH "OFFENHAUSER CHARACTERISTICS," EARLES TYPE FORKS AND THE SWING ARM OF CAST MAGNESIUM FORMING A CHAIN CASE, THE WHOLE AFAIR SWINGING ON THE AXIS OF THE COUNTERSHAFT TO ELIMINATE CHAIN DEFLECTION.

ABOVE, BOTTOM: DUTCH ON HIS BABY, A 1930 SCOTT "FLYING SQUIRREL" 600cc WATER COOLED TWO STROKER. With 5 1/:1 COMPRESSION IT DEVELOPS 33 hp AT 4500 rpm. COMPLETELY RESTORED, IT IS UNMODIFIED EXCEPT FOR A SEPARATE OIL TANK, SUPPLYING LUBRICANT UNDER PRESSURE TO MAINS AND CRANKPINS.

For the next several years, Dutch worked at nothing but motorcycle painting and striping moving from shop to shop, "saturating each area," he says. By the mid fifties he had still not touched a car, but had painted and striped thousands of bikes. After a year or so of building his reputation,

"Striping cars started as a gag when I was working Al Titus' motorcycle shop down in Lynwood," Dutch says. Then the idea ballooned. He was hired to stripe some custom jobs for one of the auto shows, an while there was approached by a man known as the Crazy Arab who thought it could be worked into a full time occupation. Dutch didn't believe it, but he tried it, and for the next three years he worked at it until "it nearly drove me out of my mind."

When Von Dutch quit striping around 1958, his talents were still in great demand. Customers all over the country had heard of him, and cars had come as far away as the East Coast to be striped. Moreover, when a car owner came to him, he didn't tell Dutch what he wanted: he just told him how much time he was willing to purchase. The designs were up to Dutch, and some of them were as wild and far out as his eccentric imagination. He had hundreds of imitators, and when you went to a body shop to inquire about such work, you didn't ask if they knew how to stripe, you asked if they knew how to "Von Dutch."

Despite this, Dutch never made any money from striping, because money is something he hates, as unorthodox as that sounds. After a year or so of building his reputation, he doubled his hourly rate just to weed out some of the customers. So many were coming to him that he couldn't stand it anymore. But the gambit didn't work. No matter how much he charged, he still did better work for less money than any competitor.

He could have charged much more. He could have charged $20 an hour and gotten away with it easily back then. Moreover, he could have done six or eight cars a day, if he really wanted to work at all. But Dutch is blissfully devoid of the driving force that motivates most Americans. He couldn't care less about material possessions.

"I make a point of staying right at the bridge of poverty. I don't have a pair of pants without a hole in them, and the only pair of boots I own are the ones I have on. I don't have anything else to put on my feet. I don't spend money on unnecessary stuff, so i don't have to have a lot of money. I don't need it. I keep as poor as I can and just get along. I like that. I believe that's the way it's meant to be. There's a struggle you have to go through, and if you make a lot of money, it doesn't make the struggle go away. It just makes it more complicated. If you keep poor, the struggle is simple. "

"That's why I never overcharged anybody, or made this thing commercial. You can't do good work if you're thinking about the money angle all the time. To me the work is important; that's number one."

Most of Dutch's custom work is now done exclusively on antique motorcycles belonging to the shop where he works. The shop is not known to have a painting department, but a fellow in North Carolina, who knew where to go, sent them a tank and fenders from a brand new Triumph to be painted as they saw fit, and Dutch did the work.

Dutch's personal motorcycle is a 1930 Scott twin, a two stroke water-cooled job that most motorcycle enthusiasts had never heard of. When something wears out on it, he manufactures the part himself. He also has a customized Honda, of which he says, "I had to paint it so I could find it. There are so many around that mine was getting lost in the crowd."

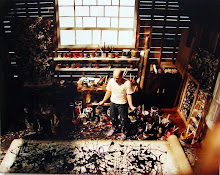

Dutch's whole life is more or less devoted to individualism, to expressing himself. He says he can no longer take paint work as a steady diet, but once you get him started on a project, you can't stop him until his imagination is temporarily worn out. He takes plain metal and turns it into a gun of his own design. Lately, he has taken to engraving designs on Aluminum fenders.

There seems to be no end to his creative aptitudes, despite his refusal to use them for profit. One of his co-workers calls him "That artistic creep," but in may ways he's the Einstein of the motor world.